I recently wrote about how both the incentive structures for academics and publishers can create problems for science. I posted it to twitter. I did not truly understand twitter until that day. Visits to the post grew exponentially up to >8,000 visitors (and yes I fit the curve: R-squared= 0.97). Yikes. That’s not a big deal for most websites, but this is a blog about vampire bat food-sharing. Perhaps more people have read that particular blogpost than all of my actual research combined.

I was both surprised and inspired by the supportive response it sparked. I’ve since talked to many people about this topic in person and online, and it’s opened my eyes to the extraordinary number of dedicated people working to improve scientific practices and publishing. Things are improving much faster than I realized.

Concerns over scientific integrity are still on the rise, as lampooned by xkcd. A recent attempt to replicate a sample of 98 high-impact psychology studies could only replicate 36-47% of them (depending on how loosely you define “replicate”)*.

[*By the way: The wrong takeaway message from that finding is that the problem is specific to psychology or the social sciences (vs other fields). Another bad interpretation is that science is less reliable (vs other sources of information). You should not trust that really cool scientific “facts” are true, but all other “facts” are even less likely to be true. So just don’t trust “facts” in general. But it doesn’t really matter that most facts are wrong. Contrary to its popular conception, science has very little to do with facts.]

But casting those problems aside, the replication crisis has many people wondering how to move towards scientific greater integrity, reliability, and transparency. The problems are numerous and intertwined. While some changes in the culture of science are going to be easy (and it’s just a question of how long it will take), other problems are deeper, and we might just be banging our heads against the wall trying to change them. Which ones should we target first?

There are three emerging scientific norms will immediately benefit everyone in science. There’s nothing holding us back except for old traditions. We need to make these happen as quickly as possible.

Step 1. All science should be open access.

How it works now: We have somehow managed to make all the worst information easy to find on the internet, and we have put much of the best and most reliable information behind paywalls (even though the authors want to give it away for free). It’s hard to think of a more frustrating lose-lose situation.

I just arrived at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, where I will have full unbridled access to some of the greatest nature and science, but no access to Nature or Science, as I’m not yet affiliated with a university. So if I need a research article, I will be asking friends on Facebook and Twitter to send me the PDF via email. But apparently this is illegal. It gets better.

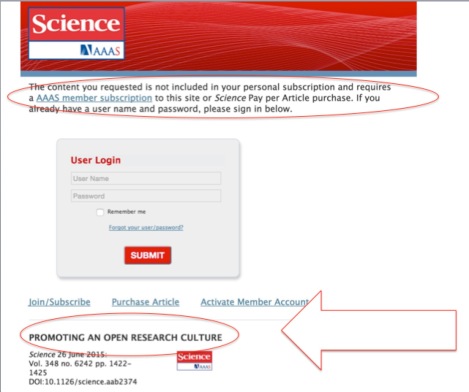

Science magazine has an article entitled “PROMOTING AN OPEN RESEARCH CULTURE” but when I tried to read it, I saw this:

Thankfully, PMC makes the article available here.

One thing that bothers me is when journals say that, for a hefty fee (>$1500), they can “make” your published article “open access”. We’ve all gotten used to this language. But scientific articles don’t become open access; that’s their natural born state!

How it should work: You type a quote or keyword from a scientific paper, and it shows up in Google or Google Scholar. From there, you can read the whole paper, look directly at the data, supplements, and the peer reviews. For a great example of how this would look, check out elife or PeerJ. You don’t have to download anything, because it’s always just available online, just like wikipedia. You don’t have to be at a university. You don’t have to ask people for PDFs. You just google it. You can read primary research on your phone, your tablet, whatever and wherever. Just like everything else on the internet. Even better, maybe you can read not only finished science, but even hypotheses and works in progress.

How are we doing: Pretty good actually. First, off there are some great new futuristic OA journals like the ones linked above. These are doing quite well. If only we would not discriminate against them for being new, these journals would quickly dominate the traditional journals, given the superior quality of their actual service. Second, the price of OA publishing for authors is dropping fast. Largely, this is because institutions are agreeing to pay for author fees. Only a couple of years ago, very few universities paid for research to be published open access. Now, many do. Finally, it’s also getting easier and easier to get free articles as authors post them to repositories. Open access is quickly becoming the norm.

Step 2. Every paper should have post-publication peer review.

How it works now: Some papers are bad (even those in the high-impact journals) and it’s not immediately obvious to people without the necessary technical knowledge. We can’t read and understand every paper, so instead we often use the journal name to judge the quality of the paper. It’s not until you read the literature more deeply that you realize that this is a huge mistake. But you have no choice, because journals have quality scores but individual papers do not.

How it should work: Every article has an individual impact factor. Reviewers and editors can give a score to the paper’s quality at the time it gets published. Over time, more reviews will accumulate. If someone has found a flaw in a paper’s logic or argument, you can see that posted alongside the paper. If there’s an error or a clarification required, the author can fix it, and the new version will be available on top of the old version (just like how we share code).

How are we doing: Ok, but not great. There are a few journals that encourage article level metrics and post-publication peer review, but not many. There’s PubPeer and similar websites popping up. Read more here.

Step 3. Institutions should encourage, rather than discourage, replication.

How it works now: Students and researchers are discouraged from replicating past work. Most journals won’t even publish replications. When people do finally try and replicate studies: Surprise! Many of them can’t be replicated.

How it should work: Imagine if graduate students were encouraged to replicate past studies as part of their training. This would also help us know what studies were accurate and which ones were flukes.

How are we doing: The project I discussed above was a huge first step. Many people are talking about replication now.

Now here are 3 problems that I believe are not going away anytime soon.

Not going away soon: “Luxury” journals, academic competition, self-interest

Why: Everywhere and throughout all of human history, people have wanted to be better than other people. In some cultures, competition is rewarded. In other cultures where competitiveness is looked down upon, many people just end up competing over being seen as the least competitive. Self-interest is deeply human too. We are not bees or ants. Rather than trying to radically change culture or human nature to make people more selfless, if you want people to vote, give blood, or donate to charity, its easier to just give the reward of social prestige. That’s what works: bring individual incentives in line with the public good.

Not going away soon: p-values, p-hacking, post hoc hypotheses, etc.

Why: The basic problem with statistics (and other maths and hard sciences more generally) is that they carry an authority that comes from many people not understanding them. If you know a little bit of statistics it’s easy to fool readers who know less than you. It’s also easy to fool yourself.

That problem is not going away soon. Let’s consider p-values as an example. Everyone who knows enough to agree, will agree, that p-values can be misleading and can encourage all kinds of problems and misunderstandings. But what is going to replace them? There is not something obviously better. In this thoughtful article entitled “The alternative to p-values”, the author gives a detailed example of how to make inferences without p-values or Bayesian posteriors. But then looking over the procedure he just outlined, the author perfectly expresses exactly what every reader is thinking:

Gee, that’s a lot of work. “I have to decide about a, b, c and all the rest as well as theta 1 and theta 2, and I have to figure how far apart p1 and p2 are to be ‘far’ apart?” [p1 and p2 are probabilities of y given various values of X].

His answer:

Well, yes. Hey, it was you who put all those other Xs into consideration. If they’re in the model, you have to think about them. All that stuff interacts, or rather affects, your knowledge of y. Tough luck. Easy answers are rare. The problem was that people, using p-values, thought answers were easy.

He then admits that any metric to replace the p-value…

can attain mythic status, like the magic number for p-values. If you’re presenting a model’s results for others, you can’t anticipate what decisions they’ll make based on it, so it’s better to present results in as “raw” a fashion as possible…

So there’s simply no “easy” way forward. People fail to grasp a simple concept in statistics, and the solution is, ironically, even more nuanced and difficult statistical concepts. In my opinion, it’s much better that students just learn how to interpret a p-value properly, rather than trying to ban them from use. The move away from p-values and towards Bayesian or other approaches is going to require more time. To get rid of p-values, an entire generation is going to have to learn how to do statistics differently.

Practices like p-hacking and post hoc hypothesizing are even harder to control because they can literally happen inside the mind of the person. Who knows for sure whether I made a hypothesis and then tested it with a correlation, or whether I saw a correlation and then made sense out of it after? Who knows how many tests I ran? How many p-values I calculated? Only me.

There are other statistical changes coming sooner, such as a move away from parametric assumptions. In the much sooner future, hypothesis-testing will be based almost entirely on permutation and simulation. That’s a good thing. But even that will take awhile, because not everyone in science is good at writing code.

Not going away soon: “Science/academia is too much work”

Why: Of course scientists work hard and are paid little; it’s a simple supply and demand issue. In biology, there are 16,000 students who start a PhD each year in the USA. So imagine 16 aspiring biologists. About 10 of them will finish their PhD and take an average of 7 years doing so. Of those PhDs, 7 of 10 will get a postdoc position. But only about 1 of those 7 postdocs will get a tenure-track job within the next 6 years. Given these odds, why do so many people enter research as a profession? I’m pretty sure most students have no idea about these chances. That’s one reason. But there’s another…

The stereotypical detective thriller Hollywood movie trope is that our protagonist gets caught up in a conspiracy and becomes obsessed with figuring out some mystery, turning themselves into an amateur detective and casting aside their other obligations and responsibilities. They end up wearing dirty clothes, sleep-deprived, in a poorly lit room, surrounded by piles of papers and coffee mugs, staring at a wall with a complex network of all kinds of facts, graphs, pictures, and newspaper clippings pinned to the wall, waiting in desperation for that eureka moment. If only they could figure out this puzzle. Then another character comes in, “When was the last time you slept?”

The best and most compelling research is like that sometimes. The best research is a labor of love and/or obsession. Without more science funding overall, we can’t all be paid the same amount as tenure track professors and have large research grants. We can only make this job less demanding at time B by moving the competitive filter point to time A. We can either make it really difficult to get into graduate school, or difficult to graduate from graduate school, or difficult to start a postdoc, or difficult to get tenure. No matter what, it’s going to be really hard at some point. Basically, there are too many people like me. I’m willing to work at whatever pay level just so I can keep working on the scientific problems I’m interested in. The rewards of doing research are creative pleasure, the respect of your peers, and the joy of finding out cool stuff. The fact you get paid enough to survive is a bonus. But that said, yes it would be nice if there were more funding for science.

How much does the public support science?

I don’t know the answer to this. Here is an interesting table on public’s trust in different institutions. Government and popular support for science has traditionally been high. Based on what I’ve seen in my own little social bubble, I thought appreciation of science was increasing dramatically, but apparently not so. In 2009, when US adults were asked whether science made their life easier or more difficult, 10% replied that science had made their life more difficult. In 2014, that number was up to 15%. [One can only hope that the responders were actually thinking that answering endless poll questions was making their life more difficult.] As Pew reports, “public appreciation of scientists’ contribution dropped 5 points from 70% in 2009 to 65% in 2013 with a corresponding uptick to 8% in those saying scientists contribute “not very much” or “nothing at all” compared with 5% in 2009.” But these trends are driven by only particular demographics. Survey data also show that “while trust in science declined between 1974 and 2010 among those who frequently attended church”, there was no detectable group-specific change in trust in science over that period among any of other sociodemographic factors examined, including gender, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.

Most people enjoy the ways technology has benefited their lives, but I’ve come across many people who have this strange idea that the underlying foundational science and technology comes from the private sector: that Apple invented the technology for the iPhone, that a company like Google created the internet, that new medicines are discovered and developed by pharmaceutical companies. The sad thing is that basic science produces pretty much every societal benefit of long-term value that is informed by knowledge, yet it produces almost nothing of immediate value. It becomes nearly impossible to see the line from the iPhone to this guy or to the underpaid, sleep-deprived graduate student at MIT with immigrant parents, or to grants from the government based on promise of military application.

It’s hard to explain the value of knowledge for its own sake. So when asked of the value of their research, scientists must choose between conjuring up stories of its future potential value [like the last line of a grant proposal] or giving a response that often sounds condescending, irritated, or self-important. Faraday, one the of greatest scientists of 1800s, was often asked something like “Ok, that’s all very interesting, but of what use is electricity?”

There are two famous replies he gave (both are snobby and perfect at the same time). The first: “Of what use is a newborn baby.” And his reply to the Prime Minister of Great Britain: “Sir, there is every possibility that you will soon be able to tax it.”

Really interesting post Gerry, with lots to think about. I think I’d quibble at the statement that scientists are “paid little”; compared to national average wage levels for instance, academics do well, whilst scientists in industry do even better. It depends on career stage though.

I was really struck by your statement that: “We have somehow managed to make all the worst information easy to find on the internet, and we have put much of the best and most reliable information behind paywalls”.

What you say is true, but then the question is “who is the best and most reliable information aimed at”? If it’s other scientists then most can gain access via institutions or via personal contact with the author, or through ResearchGate, etc. If it’s the general public then we have a deeper problem. Although they have every right to access this information (given that their taxes and donations often fund it) they probably do not have the technical and specialist knowledge to make complete sense of it.

In this case, how do we make the information available to the public? One way is by producing articles and blogs aimed at a broad, general audience (as you’re doing here) though some scientists baulk at the thought of “promoting” their own research in this way. But I see it as an important component of democratising science and something which more scientists should engage in: it’s good for them, good for society, and good for science. One of my most viewed posts dealt in part with this topic: https://jeffollerton.wordpress.com/2015/01/08/what-do-academics-do-once-the-research-is-published/

LikeLike