Last month, postdoc May Dixon, former postdoc Basti Stockmaier (now faculty at University of Tennessee Knoxville), and his partner Claire Hemingway (also now faculty at UT Knoxville) went to Costa Rica to scout a new field site for tracking contact networks between vampire bats and cattle. Below is a summary of a trip report by May Dixon:

Our goal was to see how the site measured up to our ideal field site: Somewhere with (1) a small group of cattle that are easy to corral and move around, (2) a colony of <100 vampire bats that (3) feed exclusively on those cows and (4) convenient facilities and accommodations nearby. The closer we can get to this ideal, the closer we can get to creating a complete ‘bat-cow’ contact network by putting proximity sensors and GPS tags on the bats and the cows.

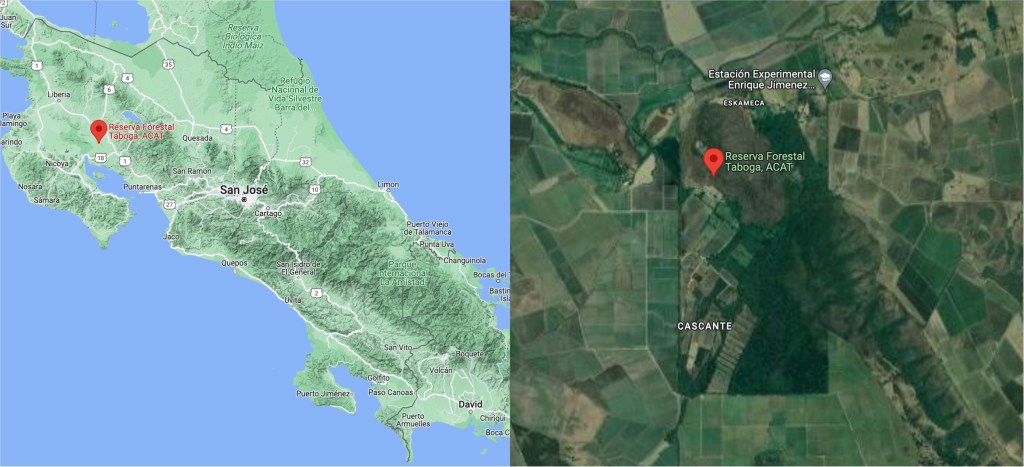

The site we were checking out is the Taboga Forest Reserve in Guanacaste, Costa Rica (below). The reserve consists of 2.97 sq. km. of protected tropical dry forest and sits within an experimental farm that also boasts palm forests, mixed pasture with around ~20 cattle, sugarcane fields, and even tilapia ponds.

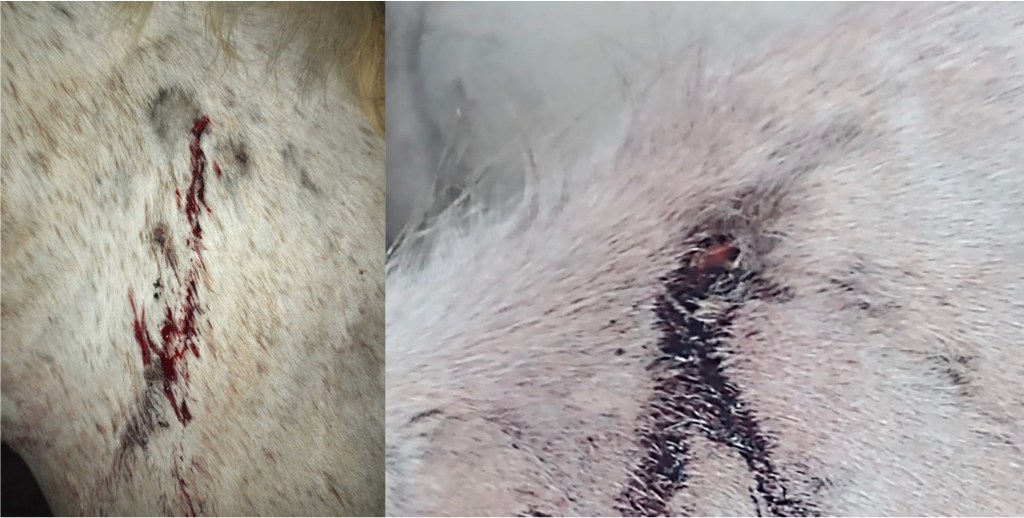

Thore Bergman, Jacinta Beehner, and Marcela Benítez run Capuchins @ Taboga there, a long-term research project studying the cognition and behavior of wild white-faced capuchins. At any given time, there are a dozen researchers living at the field site, spending every day working together to follow one of several well-known groups of monkeys through the forest, identifying them by sight, and meticulously documenting their behavior. We were intrigued by Taboga, because while there are other cattle in the surrounding areas, the immediate vicinity is surrounded by cane fields, and the reserve has the only mature forest in the area. We suspected that the vampire bats might roost in trees in the mature forest and fly to the experimental cattle and horses to feed at night. Before arriving at the site we received promising pictures of the horses and cattle with characteristic bloody bites on their necks (below).

Aside from assessing the general suitability of the site, our main goal for the trip was to find a roost of vampire bats that fed on the experimental cattle. Our first strategy was to place mist nets around the cattle and catch bats as they came to feed, to place radiotrackers on their backs, and then to release them and use radio telemetry to find them in their roosts during the day. Our second strategy was just to walk as much of the forest as possible to try to find bat roosts. We worked with Alex Fuentes (below), a long-time field technician at the station who knows the forest incredibly well.

The second strategy paid off immediately: Alex already had some likely trees with hollows in mind. Thanks to him, we found excellent vampire bat tree roosts on the first day (below), as well as many other beautiful trees with other bats inside.

We also had no problem catching vampire bats around the cattle (below). Over two nights of catching, we caught 24 vampire bats, and placed 16 radiotags on 13 females and 3 males. However, we had a hard time refinding these bats. We did not hear or see any of them inside the roosts we knew about, and couldn’t hear their signal anywhere we searched over the next 6 days. We found lots of other roosts with other animals inside (other bats like Micronycteris, Trachops, and Saccopteryx, and opossums, anteaters, iguanas, and cat-eyed snakes), but no tagged vampire bats. Our detection range was very small in the forest, and would be even smaller if the bats were deep inside a thick tree, so we thought we’d have to be within 6-30 m to hear them.

On our very last afternoon, Alex and I checked out a patch of forest that we hadn’t canvased yet. The monkeys don’t visit the area often, but Alex thought that there were some good big trees. And he was right! After an hour, we heard the first real beeps from a radio tag, and only ten steps away, we found their roost: a beautiful hollow Guayabón (below) with 30+ vampire bats inside, including 3 of the females we had tagged. It was easy to imagine the bats leaving their roosts and flying up one of the two canals that run directly through the forest to the cattle pasture.

In total, we found 6 vampire bat roosts with 3-50 vampire bats each. One of these definitely feeds on the cattle from the reserve, and we still do not know where the other bats feed. We also found another 16 tree roosts that contain at least 5 bat species: Saccopteryx bilineata, unknown Emballanuridae sp., Trachops cirrhosus, Micronycteris microtis and Carollia sp, (likely C. perspicillata). In abandoned buildings on the property, we identified Saccopteryx bilineata, Carollia perspicillata (likely), Glossophaga soricina, and Balantiopteryx plicata (below). All the above species provide important services such as eating insects, dispersing seeds, and pollinating flowers. Overall, we saw about 10 bat species from 5 foraging guilds at the reserve.

We think that this field site is a great candidate for future vampire bat research. Beyond the convenient cattle and the vampire bat roosts, we also loved the bustling community of people studying social questions similar to ours. It was fascinating to learn about the dramatic social lives of the capuchins, and even on our short trip, we benefited hugely from their logistical and moral support.